From Glockenspiels to Butterfly Wings: How Sufjan Stevens Crafted the Album Behind Broadway’s Illinoise

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

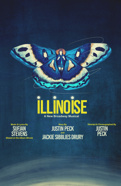

On April 24, the fleet-footed, heart-filled theatrical event Illinoise opens at the St. James Theatre. With direction and choreography by Justin Peck and a story by Peck and Jackie Sibblies Drury, the show is a dance-driven theatricalization of the concept album Illinois, released by the indie-folk singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens in 2005.

The show stars vocalist Shara Nova, who provided backing vocals on the original album, along with new arrangements of Stevens' songs by composer, pianist and frequent Stevens collaborator Timo Andres.

With their lush, quirky orchestrations and relentlessly referential lyrics, Stevens’ songs sound like nothing else on Broadway this season. That’s no surprise, really, since the original album itself sounds like nothing else released at the time or in the years since.

Now that the show has landed on Broadway, it's the perfect time to explore the story—with insights and memories from Nova and Andres—behind one of the singular records of the early 2000s, by one of popular music’s most intrepid artists.

IN 2003, SUFJAN STEVENS, a budding New York-based singer and multi-instrumentalist with an MFA in creative writing and a fondness for trucker caps, announced his intention to write and release an album for each of the 50 U.S. states. Music lovers were paying attention; Stevens had just released Greetings from Michigan: The Great Lake State to appreciative reviews. (Pitchfork called it a “frost-bound tone poem.”)

While Greetings from Michigan had been a pretty picture postcard of a record, Stevens envisioned the next album in the series as something more sweeping and panoramic: “a kind of historical survey,” a “movie soundtrack but without the movie,” sprawling in scope and encyclopedic in its range of references. Stevens set his sights on Illinois, recognizing the Prairie State and Chicago as “the center of gravity for the American Midwest.”

He didn’t know the place very well personally. He’d driven through a few times, apparently creating “important” (not specified) memories in Peoria and Chicago.

Stevens spent the last six months of 2004 deep in research. He read Saul Bellow and Carl Sandburg (“Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning,” Sandburg wrote in 'Chicago'); Frontier Illinois, a book tracing immigration patterns in the state; and biographies of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln. He pored over local newspapers and picture books, even police records, and read up on such Illinois esoterica as the Superman statue in Metropolis and exotic animal sightings in DeKalb. He became particularly interested in Illinois architecture, ghost towns, the 1893 Columbian Exposition and the war heroes Stephen Decatur and Casimir Pulaski.

Stevens solicited Illinois stories from friends as well as strangers in internet chat rooms: tales of farm clubs, scout camps, pig races, Pullman carts and beauty pageants. He took personal trips to the state too, reportedly taking the time to visit small-town chambers of commerce.

Stevens poured all of these wildly diverse ingredients into his lyrics—often to trippily psychedelic effect. (Songs about Springfield, Pittsfield and Carlyle Lake didn’t make the cut.) His literary approach owed something to his interest in psychogeography and the writings of William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams and Flannery O‘Connor. “They were writing about things that were uniquely American," Stevens told The Guardian in 2005, "and yet they seemed also much more universal, and their writing focuses on abnormalities, the grotesque, the supernatural… but it’s all very much rooted in the American landscape.” At the same time, Stevens’ lyrics explored a more personal emotional landscape—or, as he would put it in one couplet, “the state that I’m in, the state of my heart.”

Stevens was busily charting new musical territory too. “I think the reason why this music stands today is that the words were not leading the melodic material,” said Nova—a performer in her own right, under the name My Brightest Diamond. “The melody and the form lead everything.”

First and foremost, Stevens drew on his indie-folk roots—his folksy, hammer-on banjo-plucking is a core sound on the record—but he also took considerable inspiration from the looping instrumental patterns of the minimalist composers Terry Riley, Philip Glass and Steve Reich, particularly Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians.” At the time, Stevens was listening to pieces by Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff and Grieg, as well as baroque opera and vocal cantatas.

The new songs vacillated giddily between time signatures. “They Are Night Zombies!! They Are Neighbors!! They Have Come Back from the Dead!! Ahhhh!” fluctuated between 5/4 and 6/4; "Jacksonville" alternates 7/4 and 4/4; while "Come On! Feel the Illinoise! (Part I: The World's Columbian Exposition – Part II: Carl Sandburg Visits Me in a Dream)" shifts between 5/4, 7/4 and 4/4, among others. (In Stevens’ Illinois, even a song title is an event.)

Stevens recorded most of the album in a studio in Astoria, Queens, using his own antiquated eight-track recorder and engineering and producing himself. He would lay down a foundation of banjo, acoustic guitar or piano, then proceed to layer on one instrumental part after another, personally playing the vast majority of instruments, including accordion, flute, glockenspiel, oboe, recorder, alto sax, sopranino sax, sleigh bells, vibraphone, a Casiotone MT-70 keyboard and various other percussion instruments.

Stevens did enlist a proper string quartet—crucial string parts for the record were recorded in a violist’s Washington Heights apartment—as well as a small choir’s worth of singers, dubbed the Illinoisemakers, who provided background vocals as well as handclaps.

Stevens spent about four months like this. “I just kind of went crazy,” he said.

The resulting record is a happy collision of chamber orchestra and rock band, with straight-ahead folk ballads hanging out with more experimental instrumental pieces. There’s a baroque intricacy to the music, with occasional moments of euphoric grandeur—but also an endearing scrappiness to the whole affair. “There was a kind of casualness in order to preserve the kind of spontaneity of it,” said Nova. “It was not overly tweaked and tweezed. It was like, one take, maybe two. That's good enough. It wasn't overwrought.”

“One of the reasons that it’s such an indelible artistic statement is that it doesn’t adhere to what we think of as genre boundaries,” Timo Andres, the arranger and orchestrator of the new show, said of the original record. “There are so many things in it.”

Stevens even cited Broadway as a point of reference, though the effect was perhaps more off-off-off-Broadway. “There are a couple moments on the album that are a little bit kind of tongue-in-cheek musical theater, I would say,” said Andres. “But it feels like it's almost like a high school gym musical theater production.”

"I just kind of went crazy" –Sufjan Stevens

Over 21 tracks and 74 minutes, Stevens led the listener on a fantastical and emotional musical road trip. Summing it all up, Andres said, “There’s always something interesting happening around the corner.”

Illinois was released on July 4, 2005. Selling 9,000 copies in the first week, it landed on the Billboard 200 and was eventually certified gold. It turned up in numerous end-of-year lists, in the book 1000 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and, later, Pitchfork’s ranking of the best albums of the decade, where it placed sixteenth.

On tour, Nova remembers, a pleasant scrappiness persisted: Stevens had personally hand-sewn cheerleading costumes and butterfly wings for the members of his troupe to wear. While touring the record, Nova and the other band members realized the album had become a phenomenon. “People were climbing the walls to get into the shows,” she said. “It was a madhouse. When we were at Bard the students were literally hanging out of the windows.”

(Photo: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images)

In the end, the so-called 50 States Project turned out to be a cunning and effective publicity stunt. Arguably, though, Stevens’ musical endeavors only grew more audacious: two box sets of Christmas music; a mixed-media piece, commissioned by BAM, honoring the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway; the electronic-pop fantasia The Age of Adz; a collaborative album about the solar system; and music for multiple ballet premieres, including Justin Peck and the New York City Ballet. In 2023—just weeks after it was revealed Stevens was in treatment for Guillain-Barre Syndrome—he released Javelin, a suite of ten love songs that earned some of the most glowing reviews of his career.

Nearly 20 years since its release, the music of Illinois is connecting with live audiences all over again. For those who were listening back in 2005, the new show is a nostalgic reminder of the original record’s idiosyncratic specialness and the restlessly inquisitive musical mind behind it.

It’s also an invitation for audience members to take a trip back through their own memories. A lot can happen in 20 years. As Stevens once put it: "All things go"; "all things grow."

“I feel a certain sense of satisfaction that I can participate and be part of the next iteration,” said Nova. “We’ve come a long way.”